Let's imagine an alternative metaverse...

Society's entanglement with technology has brought forth unprecedented harms — do we really want to risk augmenting these in a metaverse?

Hi there! Welcome to the third monthly series of Untangled. Last month I offered some unsatisfying solutions to the problem of Facebook, which ... was referenced in Congress. NBD. Then I interviewed Daphne Keller about the problem of amplification, the tradeoffs of regulating reach and speech, and what she would tell her teenage self about life.

If someone forwarded this to you — and they aren't a member of my immediate family — that's great... and surprising. In any case, all you have to do to earn their life-long love and respect is to become a subscriber.

This month I’ve decided to write about something we’re all not at all tired of reading about and totally understand: the metaverse! Happy new year! 🎉

TW: this issue of Untangled discusses online sexual harassment against women, including descriptions of groping and other intrusive and unwanted behavior.

In 2017, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg proclaimed that Oculus, its virtual reality headset, had the chance “to create the most social platform ever.” Just one year earlier, a gamer under the pseudonym Jordan Belamire wrote about her experience of being groped in virtual reality. She was playing QuiVr — a game where your gender is only made (potentially) explicit when you actually use your voice. Belamire spoke out loud, and then someone with the handle BigBro442 began to grope her avatar with their free hand. When she asked them to stop, they didn't.

This goaded him on, and even when I turned away from him, he chased me around, making grabbing and pinching motions near my chest. Emboldened, he even shoved his hand toward my virtual crotch and began rubbing.

Yes, that's right: all the bad stuff that happens in real life can and will happen in VR too — what a shocker.

Now, Meta, along with a number of other companies and crypto enthusiasts, are trying to turbo-charge the development of 'the metaverse' that will (in theory) integrate VR, AR, gaming, facial recognition, cryptocurrencies, and NFTs, among other technologies, to create a more "immersive" Internet. You'll feel "presence" and experience "empathy." It'll be great! For some of you. Maybe.

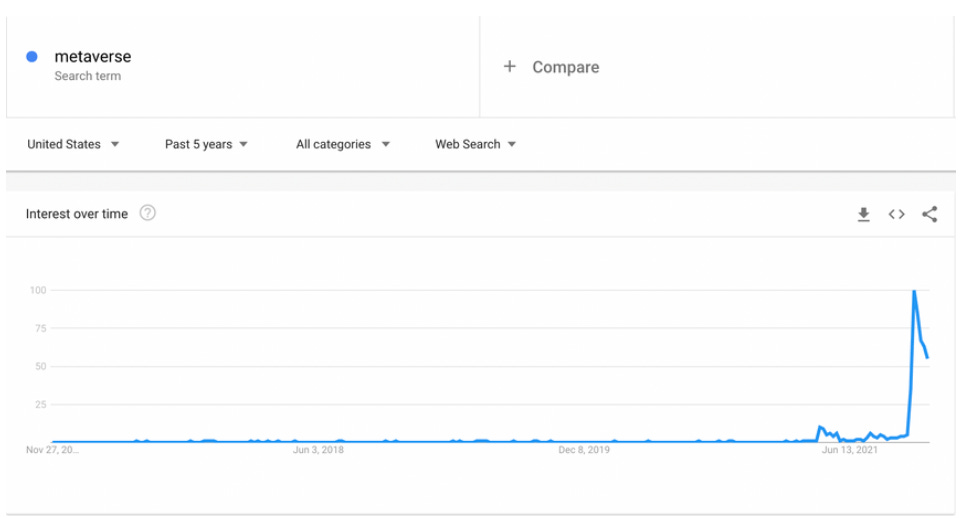

Of course, the metaverse isn't really a thing yet. Hell, no one talked about it until April of this year, when all of a sudden, we talked about it. All. The. Time.

So, we find ourselves in a moment where we can shape what it means before it becomes fixed in our imagination. If you could go back in time, right before the start of social media, and call bullshit on the idea that 'staying connected' is inherently good, and change the way we govern our own data, would you? Yeah, me too.

I don't want the metaverse to become a thing. I think the societal harms will likely far outweigh any benefits. I also think the establishment of a metaverse is inevitable... because capitalism! Whatever form the metaverse takes, we must address the social and economic inequalities that it will perpetuate: How will our most personal data be governed? To whom will value accrue? Who will be subjected to targeted harassment and abuse? Because for many, the "most social platform ever" just means new dimensions of so-called 'unintentional' harms.

To help us through this, we must ask: who shapes how we think about the metaverse, and from whose perspective is it designed and built? Well, I've observed three prevalent influences on our current understanding of the metaverse. Let's dig into those a little before we look at alternatives.

The first is dystopic sci-fi. That's not a joke — or at least not a very good one. It's nevertheless impossible to read an article about the metaverse without mention of sci-fi author Neal Stephensen and his 1992 novel Snow Crash. In Snow Crash, the government is no longer relevant, city-states are ruled by big business, inequality has run rampant, and the metaverse offers a digital distraction; an escape into a virtual world of abundance and play. It's bleak y'all. Users can pay more for higher resolution avatars because class-based inequality exists in the virtual world too. Some users, known as gargoyles, become so enamored with the metaverse that they permanently plug themselves into it. Unsubscribe.

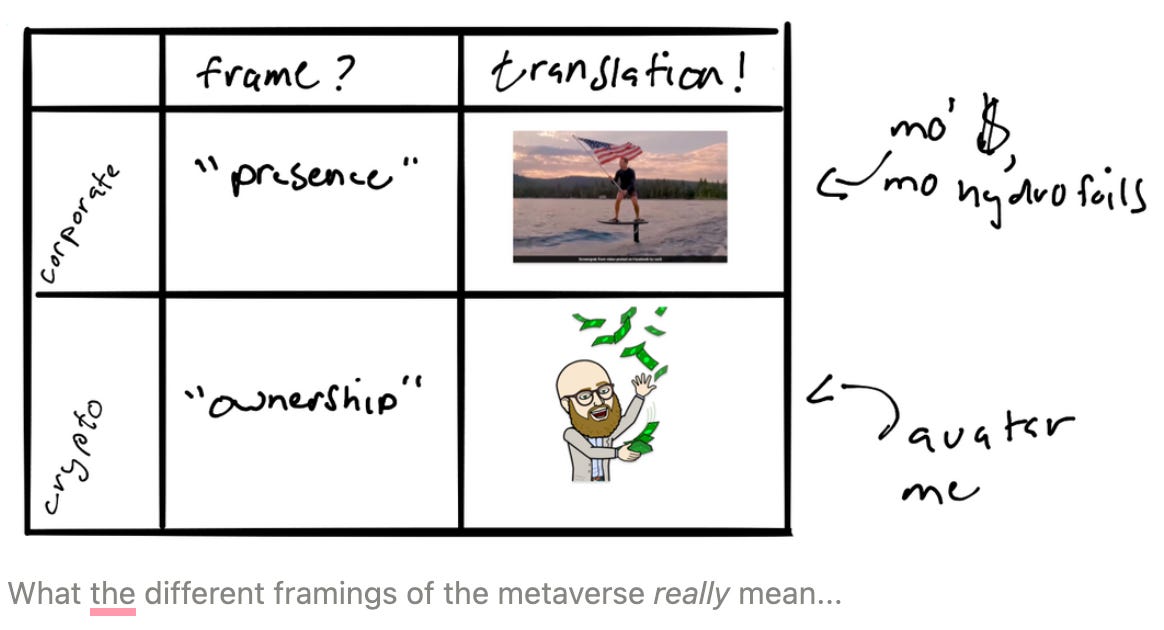

Then there are the corporate evangelists of the metaverse who focus on "presence," and "immersive experiences." Satya Nadella, CEO of Microsoft, has said the metaverse will bring "real presence to any digital space," adding that "human presence is the ultimate connection." Chief metaverse evangelist, Mark Zuckerberg, said that the metaverse would be "more natural and vivid," and give people a "stronger sense of presence." Harkening back to how he once spoke about Facebook, he added, the metaverse would facilitate "the most important experience of all: connecting with people." Fool me once, shame on you. But fool me twice?

📱For Meta, the metaverse is its platform strategy. It's currently vulnerable to Apple because Apple can and has implemented changes to iOS that impact Meta's business. Meta needs the equivalent of its own iPhone: a device that other companies and developers need to build upon. That's why they bought Oculus in 2014 — the only problem is that few people actually own an Oculus. So, Meta is pursuing an enterprise strategy: if consumers aren't buying the headsets, companies will have to kickstart demand.

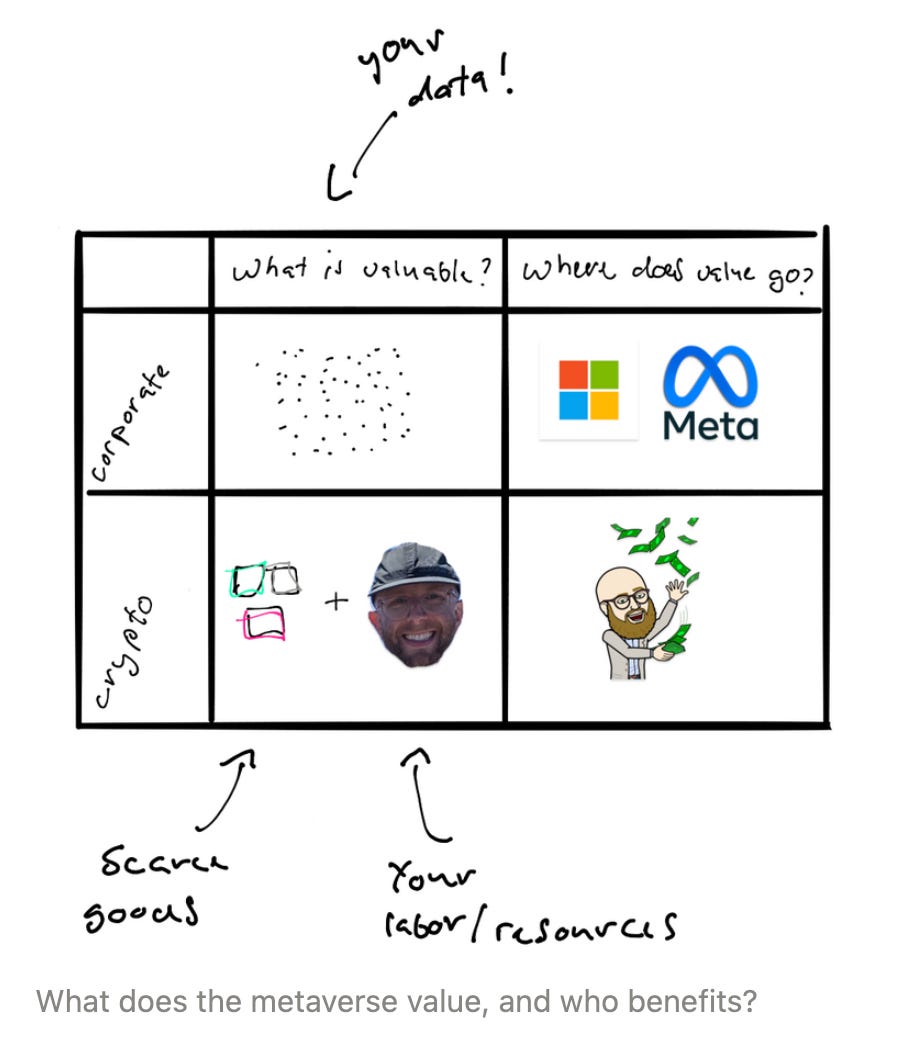

This corporate evangelist framing of the metaverse is just a sheen over yet another data capturing activity. "Immersive" is just a positive way to describe an invasive experience. "Presence" wants you to forget that it is your sensory and biometric data that create such a feeling. Don't let these words confuse you — for the corporate evangelists, the metaverse is a fight over users and their data. VR enables the collection of biometric data like eye movements, body tracking, facial scans, voiceprints, blood pressure, and heart rate. AR enables the collection of data about everything and everyone you look at, without their consent. This data will be used to sell you ads and, if history is any indication, be repurposed for a host of things like setting your insurance premiums.

The third group of influencers includes crypto enthusiasts — venture capitalists, libertarians, and techno-solutionists — all trying to bring a "decentralized" metaverse into existence. If you don't know why I'm putting "decentralized" in quotation marks, stop reading this piece and read my other piece about how decentralization in crypto is more of a veil and less of a reality. They also want to monetize more of the digital world — but it's not your data that they're after, it's artificially scarce digital goods.

Influencer-in-chief Marc Andreesen sees inequality as inevitable, and maintains that attempts to make progress in the real world are futile (yes, really) — so, best to create a virtual world of abundance instead. At the heart of this creation of digital abundance are non-fungible-tokens or NFTs. Think of an NFT as a digitally scarce good or a unique ID for your digital assets. In web1 and web2, we were able to copy information infinitely, but now crypto or 'web3' promises the "ownership" of digital goods (it's still disputed whether NFTs constitute legal ownership). The use of smart contracts, which remove the need for an intermediary like Spotify, combined with NFTs means musicians and other creators will receive a greater cut from the sale of their work. It also means that rich people can do crazy things like buy a virtual yacht for $650K or a plot of digital land for $2M.

If "presence" and "immersive" represent the corporate frame, then "ownership" and "economic empowerment" represent the crypto alternative. Crypto enthusiasts emphasize that smart contracts, by removing the middleman, enable new economic models like "play-to-earn" gaming, where gamers earn significant sums by playing games. As you earn tokens, you can do things like buy new avatars or digital real estate.

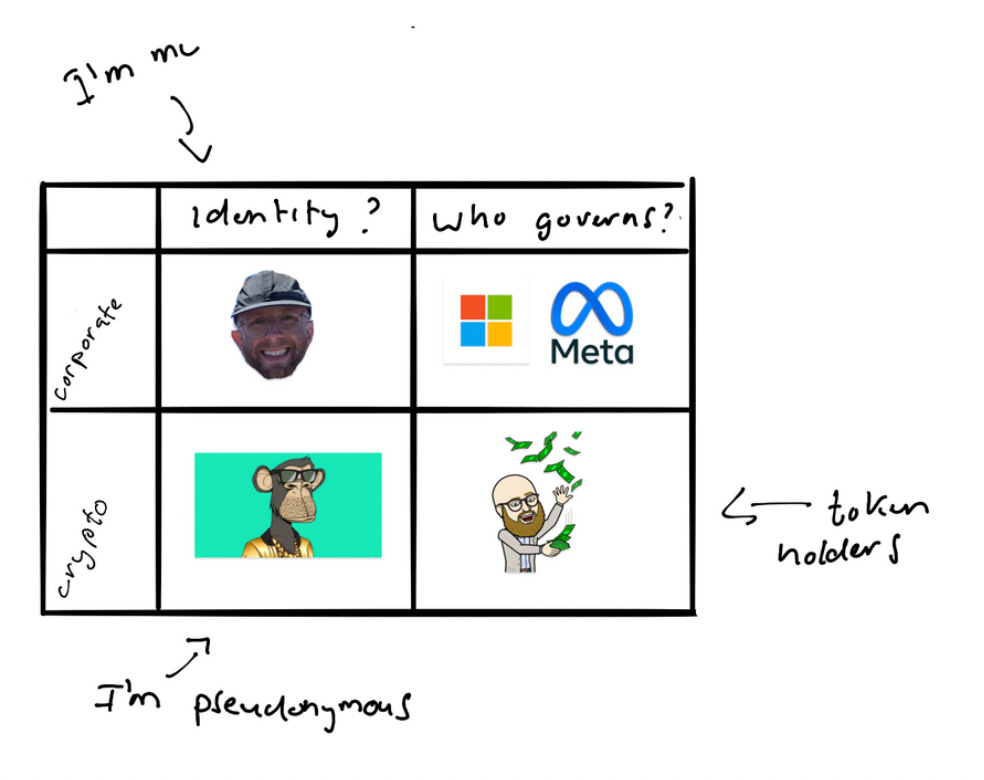

Whether this digital abundance translates to real economic empowerment is TBD. That depends on crypto governance — those with governance power, which today roughly translates to those with more tokens, will determine how these worlds evolve. And perhaps it's obvious to say, but whether owning more tokens translates into economic empowerment is also mediated by the decisions governments make about how to tax and regulate these systems, and how social structures like race, gender, and class influence participation in these virtual worlds, and the material distribution of wealth and resources IRL.

🥸 One conundrum the crypto community will confront has to do with identity. The crypto community privileges pseudonymity. On crypto Twitter, for example, first and last names are often replaced with .eth or .sol. People's pictures are replaced with cartoon jpegs. Pseudonymity helps people who might need to protect their identity (e.g. an oft-persecuted human rights advocate) while also enabling unaccountable harassment.

So, the sci-fi metaverse promises an escape from a deeply unequal reality. The corporatist metaverse is a scramble for ever more personal data. The crypto metaverse is a land grab for digital goods and, well, digital land. What all of these visions share is an acceptance or entrenchment of the status quo. But we can and should imagine a metaverse that more directly challenges the status quo. Or, you know, just forget this whole metaverse thing and move on with our lives.

How can we imagine an alternative metaverse?

In her influential article ‘Strong Objectivity,’ Sandra Harding, a philosopher of feminist and postcolonial theory, argues that to see and analyze a system clearly, one must assess the system from the perspective of those excluded from it or harmed by it as a result of their social locations.

So, if we are indeed looking at a metaverse that will be 'the most social platform ever,' surely as many social groups as possible should have a hand in forming it. Strong Objectivity can help us imagine and build a metaverse that works for people who are routinely excluded from decision-making in these systems and disproportionately harmed by them both online and off.

We also have design justice, which prioritizes the expertise of people who are harmed by these systems, in order to reduce and hopefully interrupt the reproduction of oppression. Sasha Costanza-Chock, Director of Research & Design at the Algorithmic Justice League, argues for "an approach to design that is led by marginalized communities and that aims explicitly to challenge, rather than reproduce structural inequalities." In such an approach, members of marginalized communities would lead the design and governance process. They would make decisions about how their data is governed, which technologies are used and banned, how abuse is handled, and how their identity is captured. Further, Andre Brock, an Associate Professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology, has shown in his work how marginalized communities can and do develop creative, anti-oppressive cultures and practices that go against the grain of these systems' biases, exclusions, and extractive designs that we can draw inspiration from. And there are groups imagining anti-racist, anti-ableist alternative futures right now.

If we don't seriously consider these alternatives, harm and harassment will continue to impact the same groups of people — namely women and people of color. Our virtual spaces are already dominated by ideas that were clearly put forth by non-marginalized folk. Lisa Nakamura, professor at the University of Michigan writes, “Racist representation within games can be found in every genre: simulation games like the immensely popular Civilization series depict non-Western culture as shot through with superstition, cruelty, and irrationality.” She goes on to argue that “Black women, in particular, were very rarely represented in video games,” and when they were “they were much more often depicted as the victims of violence than characters of any other identity.”

These patterns are not limited to games: Mary Anne Franks has documented similar findings in virtual reality. She argues that "virtual" sexual assault has been around as long as virtual communities have existed, documenting instances of "avatar rapes." I will not detail examples of these, but I will tell you that accounts of these situations exist online, and you can find them yourself. As a cis-gendered white man, it's not my job to regurgitate stories of abuse — rather, it is my job to urge people like me to put in the emotional labor and sit with the implications of these stories.

Another key dimension of the metaverse is the use of AR and facial recognition. Researchers like Joy Buolamwini, Timnit Gebru, and Deb Raji have shown that facial recognition systems are biased by race and gender, and scholar Simone Browne has demonstrated that they are informed by histories of anti-Black surveillance and legacies of debunked 'race science.' Yet these systems continue to be used in a number of contexts, including by police departments, leading to a number of wrongful arrests. This is in part why a coalition of civil rights groups have called for a federal moratorium on the use of facial recognition. Even if it didn’t have these problems, facial recognition technology would still erode anonymity in public spaces and invite surveillance and control. Imagine AR glasses, enabled with facial recognition, pointed at the world — that would create a real-time surveillance feed that no one in front of the glasses consented to. We already know that basic geolocation apps increase and facilitate the stalking and harassment of women; we also know that women are nearly 2X more likely to be the victim of the unauthorized sharing of private or sexually explicit images. Now imagine that someone can create a live-feed recording of you by tilting their head in your direction and blinking an eye.

A design justice framework would put women and people of color in charge of designing and governing the metaverse. This is not a perfect solution — Costanza-Chock notes that even designers from marginalized groups sometimes make the same normative assumptions about users. They too are influenced by the cultural biases and norms that make certain categories the default — that the user, for example, is assumed to be straight, cisgender, not disabled, and speak English. Moreover, participatory design practices have a history of being exploitative, and often lead to "participation washing" or reflect "predatory inclusion."

The thing is, there's nothing stopping Big Tech from hiring people with whose social locations allow them to identify the variety of injustices that are built into everyday systems into leadership roles — they just choose not to; there's nothing stopping the creation of DAOs that govern themselves according to democratic values and anti-oppressive goals instead of economic incentives — but no one seems to want to do that at the moment.

We need to reframe and reprioritize whose expertise and experiences shape discussions of the metaverse. When was the last time you read about the experience of Black women in AR, VR, or gaming in an article about the metaverse? When was the last time a piece of tech wasn't shaped to exclusively accommodate — and accrue profit and resources for — people like me?

These questions are not rhetorical — I don't know the answers; nor am I the right person to look at solutions to these problems, because these problems mostly do not affect me. But here's what I do know: most of the time, the results of the entanglement of technology and society are impossible to predict. That's not the case here — the metaverse is an assemblage of technologies and systems that are very clearly, in the present, benefiting some and disproportionately harming the many; and these systems don't show any signs of changing. We don't have to guess what's going to happen; it's happening right in front of us. The consequences of a metaverse under these terms are neither mysterious nor unknowable — think about that next time you hear the phrase 'unintended consequences.'

So, cis-gendered white men: it's our responsibility to challenge ourselves to research and understand these issues. We must interrogate our own blind spots and the ways we've internalized or reinforced systems of patriarchy and toxic masculinity; ask hard questions of ourselves, really listen with openness and understanding, learn to communicate and collaborate across differences, and then act in solidarity. Above all, we must follow the lead of those already enacting less oppressive digital practices and holding open the potential of a better future. It's an unsatisfying start, but it's a start.

Thank you to Katie Detwiler for providing comments on an earlier draft and to Georgia Iacovou, my editor.