Crypto is not decentralized

Because technical decentralization does not decentralize power — it only hides it

Hello readers and welcome to the first ever issue of Untangled 🥳. Thank you for being an early subscriber, and if this email was forwarded to you, consider becoming a subscriber too.

Before we dive in, a quick note about format:

On the first Sunday of the month, you'll receive a post where I embark on a deep exploration of a particular topic or concept.

After publishing, I will share an interview with a relevant field expert, where we discuss potential solutions relating to the topic a week or two later. I'll then send along some reflections on what I've learned, and questions I still have.

With each monthly deep dive, I will always open up the floor: you are invited to hit reply, tell me what you think, and even submit questions that I will use in my interviews.

I want Untangled to become a community. If you have ideas about how to make the newsletter better or a topic I should write about, tell me. If you're curious about how it's all going, let's talk. If you think one of the posts misses the mark, let me know. Oh, and definitely tell me if you like it.

And now, on with the show:

I remember the early days of social media. There was a lot of chat coming from Facebook about how amazing and world-changing it all was. Every third word I heard was 'connected'. Yes, the main sell of submitting ourselves to social media was the prospect of staying connected. I didn't think much of this back then — I mostly avoided social media. And still do, as you may be able to tell from my scant Twitter following (Help?).

Still, social media felt undeniably positive in the beginning, shielded from criticism by the promise of how 'connected' we were all going to be. In the ivory tower that I often refer to as retrospect, we probably should have listened to those who were asking questions like, 'is it a good idea to connect the world on one platform?' Or, 'does maintaining consistent online connections, actually lead to genuine human connections?'

Now that we've entered the cloying late stages of web 2.0, I think it's safe to say that social media's promise of 'staying connected' didn't quite work out as expected.

🤫 Okay but: what does this have to do with crypto? Well, after reading everything I could about it over the last year, I've come to realize that where social media promised 'staying connected', the world of crypto has promised d e c e n t r a l i z a t i o n.

Decentralization wasn't always a crypto buzzword

The first thing I noticed after diving into crypto was that the space contained lots of bros who don't like governments or central banks (here's looking at you Bitcoin Twitter!). But the second much more prominent thing was the prevalence of the word decentralization. It was everywhere: decentralized finance (DeFi); decentralized applications (dApps); decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs); the list goes on. But the more I read about it, the clearer it became that even though they believe deeply in it, the crypto community cannot agree on what decentralization actually means.

The one thing they can agree on is that decentralization sounds like a good thing. It's like the antidote to centralized power, which is a bad thing. It conjures a utopia where individuals are unburdened and uncensored by centralized authorities, like big tech and big government. (To be clear — there are a number of thoughtful thinkers in crypto who don't think decentralization is the be-all and end-all.)

Whatever it may sound like to us now, decentralization is actually a pretty old concept: perhaps you can dust off the part of your brain that remembers it from the days of web 1.0. Tim Berners-Lee said that "it had to be completely decentralized" in 1999, when referring to the internet, adding: "that was the only way a new person somewhere could start to use it without asking for access from anyone else."

In fact, as early as 1996, John Perry Barlow wrote about the independence of cyberspace:

We are creating a world where anyone, anywhere may express his or her beliefs, no matter how singular, without fear of being coerced into silence or conformity. Your legal concepts of property, expression, identity, movement, and context do not apply to us. They are all based on matter, and there is no matter here.

John Perry Barlow — read in full at EFF

The values that shaped Web 1.0 were rooted in the counterculture movements of the 60s and 70s and cyber libertarianism — a philosophy that wanted to prevent government regulation of the Internet. Enthusiasts attempted to encode these ideals into the technical architecture of the web via decentralized protocols. Like TCP/IP, which allows us to anonymously send data across a network without broadcasting it — it's what makes emails work. It gives users power! There's no central authority! Decentralization! Of course, now the internet is dominated by a few trillion-dollar companies — I don't know about you, but I wouldn't call that decentralization.

Nevertheless, the concept of decentralization is alive and well in crypto. In fact, Satoshi Nakamoto (the inventor of Bitcoin) and web 1.0 pioneers share similar ideas: the point of Bitcoin was to create a system that was resilient to censorship and manipulation, that was "completely decentralized with no server or central authority" as Satoshi put it.

Bitcoin, just as with all crypto projects, is able to operate in this way because it is all built on top of a blockchain.

A blockchain is just a spicy database that enables decentralization but does not guarantee it...

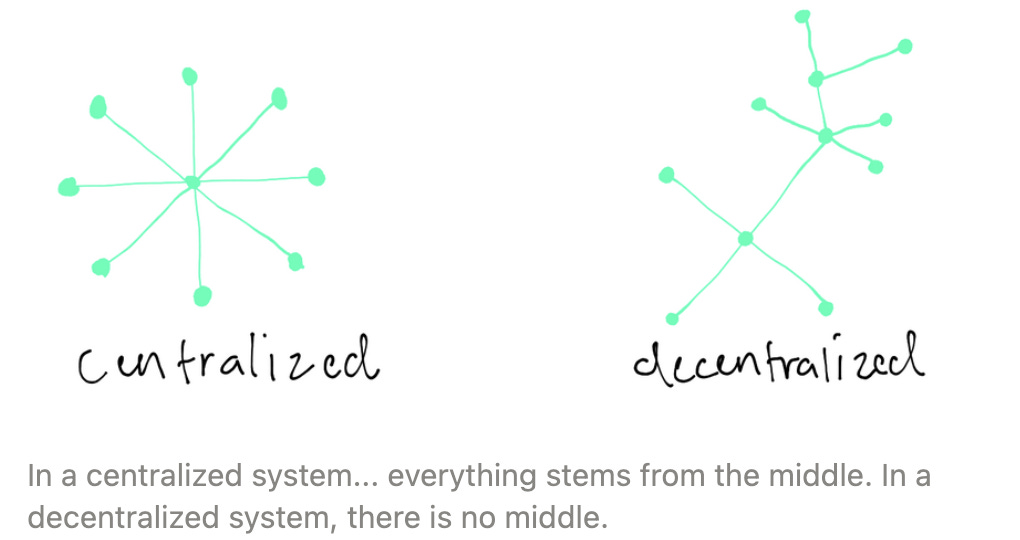

Okay so, theoretically, a blockchain is a kind of 'permissionless' database that anyone can contribute to. With a blockchain database, recorded transactions don't live centrally on a company's servers. Instead, each transaction is stored simultaneously on a network of computers or 'nodes'. The big bad middleman is dropped from the equation and replaced by a network of computers. It's decentralized! Or... is it?

As with TCP/IP, blockchain technology enables decentralization — but it doesn't mean you're going to get decentralization. Where systems and people interact, there is power. Here are the key participants and systems to understand:

Software developers who maintain and shape the protocols that govern the blockchain itself ('core developers'), and the ones who build software that runs on blockchain.

Miners use computers to process and secure transactions, and then add them to the database. The blockchain record is then maintained by the computers in the network.

Token holders own crypto tokens. The tokens can be held and used as an investment, to transact, and some give the holder certain rights. For example, governance tokens enable the holder to shape the direction of the project by voting.

Exchanges provide a central onboarding point for new crypto users.

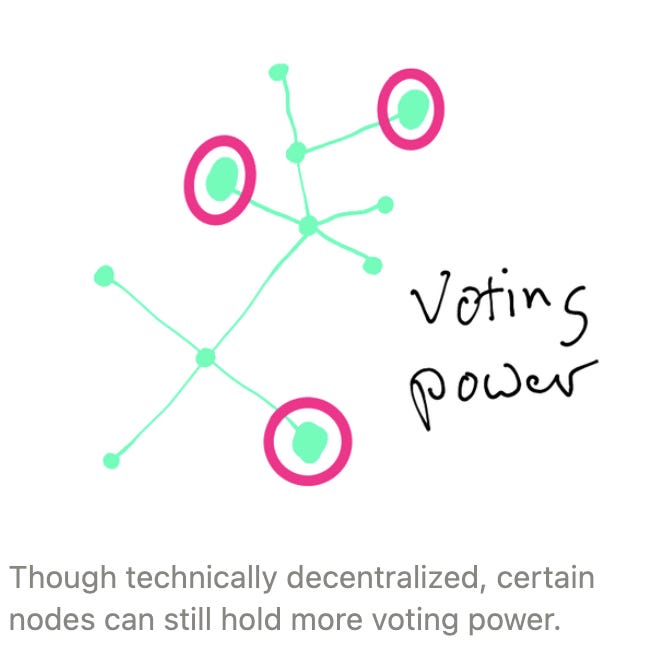

☝️ So look at it this way: if there are thousands of computers in the network but ownership of the token is concentrated in a few hands, the overall system isn't decentralized. Or what about if there are thousands of token holders but only a few core developers? You get the point. But even if the crypto community could agree on how many of each group makes a system decentralized, it would still be a conception of decentralization that doesn't include where power is.

In an excellent Tweet thread a couple of years ago, Sarah Jamie Lewis made this very apt observation:

In its simplest definition, decentralization is the degree to which an entity within the system can resist coercion and still function as part of the system. […] We need to move beyond naive conceptualizations of decentralization (like the % of nodes owned by an entity), and instead, holistically, understand how trust and power are given, distributed and interact.

Sarah Jamie Lewis, executive director of Open Privacy Research Society.

I agree! We need to understand how decisions are made and where power is prone to clustering. Are there situations where software developers are exerting informal control over the development process? Are there people who benefit more from the system than others, and do they have decision-making power? Do they sometimes have access to privileged information?

The answer to these questions is a multi-faceted yes. Case in point: in 2016, the Ethereum network suffered a hack, and so the core developers decided to move forward with a 'hard fork'. Essentially, they pressed the reset button on the network to eliminate the security vulnerability and start anew. In other words, the core developers made a centralized decision. They exerted, and in turn revealed, their position of power in the Ethereum network.

Whenever it's hard to define something, it's worth asking — who benefits from the ambiguity?

Hopefully what we've all learned here is that in the world of crypto, 'decentralization' promises one thing (or set of things), while also hiding power. Angela Walch, a law professor at St. Mary’s University, describes it as the "veil of decentralization" which “covers over and prevents many from seeing the actions of key actors within the system.”

She cites several examples where key people — usually software developers — coordinated to make important decisions at pivotal moments: such as the Ethereum hard fork described above, or even Bitcoin's bug fix in 2018, and how these were somehow not interpreted as concentrations of power. Instead, the community assumed power was diffuse. The veil held as clusters formed.

This is a human, totally unsurprising thing. Power that isn't named or seen becomes unaccountable power. The thing is, in crypto, people don't believe — or don't want to believe — it's happening.

Decentralization signals a kind of egalitarian, libertarian politics that emphasizes free choice, voluntary association, and a commitment to negative freedoms. This is true in theory. Sure, anyone can contribute to a blockchain; anyone can secure a transaction; etc. But in practice, there are significant barriers — in terms of cost and expertise — to participate as a miner or a developer. It often takes significant computing power to mine blocks, and (in case it wasn't obvious) you have to know how to code to be a software developer. Even then, you are often at the mercy of which changes the core developers choose to accept.

Another key barrier to voting power is wealth. In the Ethereum hard fork, only 4.5% of Ethereum holders participated. Furthermore, the vote was weighted by the amount of Ethereum a user held. Nathan Schneider, Assistant Professor of Media Studies at the University of Colorado summed it up this way: "rule according to wealth has so far been the norm in cryptoeconomic designs."

You may be asking, 'what good is a technically decentralized system if clusters of power form anyway?' Well, there are interesting experiments that crop up all the time. For example, the blockchain enables the ownership of digitally scarce goods or non-fungible-tokens, rewarding creators for what they make. Or look at something like Helium —you purchase a hotspot that provides wireless coverage to IoT devices, and you get rewarded for that in tokens. While experiments like these distribute value in a different way to traditional systems, the overall point still holds: none of these systems are immune from humans, who — innately or a result of societal pressures — influence and gate-keep complex systems.

This matters because the promise of decentralization is widely captivating. In the early days, it appealed to libertarians and anarcho-capitalists who didn’t trust the government to manage the economy. Over time, the ambiguity of the term has created an ever-widening tent of ideologies. Nathan Schneider has observed that "Lack of clarity around the term [decentralization] is functional, in that it enables people of varying ideological persuasions to imagine themselves as part of a common project." This ambiguity has ultimately enabled a powerful political movement — that we are still in the midst of.

The utopian vision of Web 1.0 didn't come to pass. Web 2.0 centralized power by "connecting" the world, and we're all suffering the consequences. Crypto is still in its infancy but it's clear that technical decentralization does not decentralize power. More democratic and egalitarian governance models can help to decentralize power but I'm skeptical that crypto will ever achieve its ideals.

What happens now depends on how power diffuses through crypto, the stories we tell about it, what we leave out, and whether its adherents are willing to confront the concentration of power.

📩 Move Slow & Ask Questions

Wow, you're at the bottom of the email — it's warm and friendly down here, I can assure you. As mentioned, each month I'll interview an expert or two on the topic at hand. The interviews are intended to dive deep into a single solution. I would love to co-create these interviews with you. Please feel free to submit questions — no question is too daft.

This month my interviewees are:

Angela Walch (@angela_walch), Associate Professor, St. Mary's University School of Law and Research Fellow at the Centre for Blockchain Technologies, University College London, and author of Deconstructing Decentralization: Exploring the Core Claims of Crypto Systems and In Code(rs) We Trust: Software Developers as Fiduciaries in Public Blockchains.

Nathan Schneider (@ntnsndr), Assistant Professor at the University of Colorado, and author of Cryptoeconomics as a Limitation on Governance and Decentralization: An Incomplete Ambition.

The interview with Angela will focus on how power functions in crypto and then dive deep into one novel solution: treating software developers as fiduciaries. The interview with Nathan will focus on the possibilities and limitations of governance in crypto and then discuss an oldie but a goodie: integrating political logics into crypto.

What should I ask in both of these interviews? Hit reply and I'll make every effort to include your question(s).

Disclosure - To experiment and learn, I bought tokens mentioned in this essay.

This is a provocative point of view for sure. But I think it dismisses (or excludes) the economic effects of distribution of computing and the extent to which necessity is sometimes the mother of invention (eg: TCP/IP). At every point in time across the arc of computing, some form of standard connectivity was required to hit the next plateau of scale and scale is almost never viewed absent of the cost component.

Consider for example how the scale-out approach to compute has almost entirely overtaken the scale-up approach. Scale-up (eg: AWS style autoscaling to meet inbound web demand) requires standard connectivity like TCP. Scale up (eg: an Oracle cluster or a faster chip from Intel) is proprietary. I'm not arguing that there wasn't some countercultural influence involved in the invention of technologies like TCP that achieve distribution and democratization. After all, it all came from the same counter cultural area of the country. But the driving force was to scratch a technical itch and it is very well documented.

What is true though is the cyclical push-me pull-you effect where, every time a promising decentralizing, distributing, and democratizing technology threatened the profits of the status quo, the status quo at the time moved to re-centralize it, de-distribute it, and de-democratize it as a means to preserving profits and there are many examples of this like when Bill Gates woke up one morning and realized all of Microsoft had to pivot to deal with the Internet. His fortune up until that point was built on Microsoft's control of the distributed, democratized, and decentralized effect of personal computers (just one example of the full cycle). All of these cycles -- including distributed ledgers -- have driven cost out of scale. IOW, economics.

I have no doubt of the role that counterculture played in getting us to where we are with cryptocurrencies, blockchain, and distributed ledgers. But Bitcoin also solved a massive technical problem that's intermingled with economics and that similarly drives cost out of scale. The world is globalizing with no single fiat currency and, as the world globalizes and money is exchanging hands across borders in ways that it never has before (more entities right down to individuals), the cost of that scale was once again blocker that blockchain solves for. Maybe the best way to capture characterize the counterculture you speak of is "Everyone resists the cost of participation. So where the current culture is accepting of that cost, the counterculture will find a way to work around it."

Thanks for thoughtful piece. I’m not an expert on network theory (or anything for that matter) but if we imagine decentralisation on a spectrum then surely what BTC and ETH present are networks that are more decentralised than a FB, Twitter or sub stack - and that’s enough to call the “movement” successful?

The ETH example is good, because imagine if 4,5% of FB users (30mn humans) had a say in how the news feed algorithm serves information to billions of people. That would be better than just Zuck deciding, right?

There’s always a utopian stretch goal and a few in the crowd reaching for it, but most people will be satisfied if the movement just dilutes power compared to the status quo.