Who are you?

A wonky romp through identity, classification, and power.

Hi, and welcome back to Untangled, a newsletter and podcast about technology, people, and power. If you’re reading this and haven’t yet signed up, do your future self a favor and subscribe now.

Two weeks ago, the (really great!) newsletter 1440 highlighted my podcast episode with Brandon Silverman, co-founder and CEO of CrowdTangle. Thousands listened to the episode and hundreds of you decided to subscribe. That makes me really happy. Welcome to the Untangled community 👋

Here’s what to expect:

On the first Sunday of the month, you'll receive a long-form essay exploring a tech topic that needs some untangling! This is one of those essays — get hyped for a wonky romp through identity technologies, classification systems, and power.

The next Sunday, you’ll receive an audio version of the essay and a few gifts from the internet. It’ll look something like this.

Most months, I’ll interview a relevant expert and publish it as a podcast.

Now on to the show!

Who are you? Heady stuff, I know. How we choose to identify ourselves is not necessarily something that can be expressed in a straightforward way. But there are of course identity markers such as age, race, gender, sexual orientation, and ethnicity that we — and others — can use to easily sort us into groups. Coming up with these markers and deciding how they are used is an exercise of power. Systems of classification are all around us, and how we interact with them is influenced by different technologies; the implications of a state-run survey are different from an algorithmic profile created by private companies.

This month, I decided to have a look at the ways technology has shaped and enforced systems of identity and classification. Let’s dig in.

I. You are what public institutions say you are

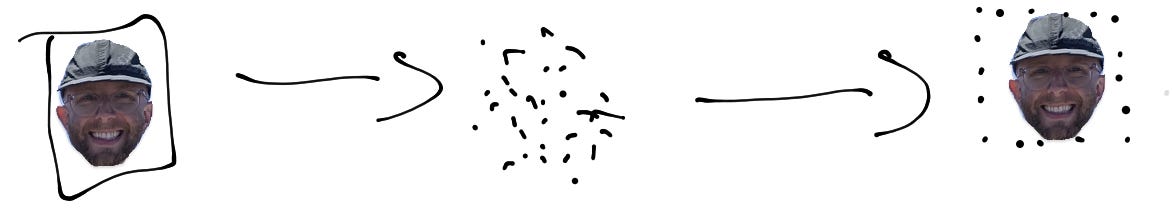

Put simply, identity technologies attempt to prove individuality, while classification systems sort us into groups. As Geoffrey Bowker and Susan Leigh Star write in Sorting Things Out, a classification system is “a set of boxes (metaphorical or literal) into which things can be put to then do some kind of work.” Here’s me in a lil’ box.

Sounds harmless, right? Wrong! As John Cheney Lippold writes in We Are Data, “The process of classification itself is a demarcation of power, an organization of knowledge and life that frames the conditions of possibilities of those who are classified.” For example, during Apartheid, South Africa developed a race-based classification system, where the Nationalist party divided and sub-divided people into categories, arguing from a “eugenic basis that each race must develop separately along its natural pathway, and that race mingling was unnatural,” as Bowker and Star write. They continue:

“For those caught in its racial reclassification system, it constituted an object lesson in the problematics of classifying individuals into life-determining boxes, outside of their control, tightly coupled with their every movement and in an ecology of increasingly densely classified activities.”

Classification systems encode moral choices, which shape one’s opportunities in life. Each category “valorizes some point of view and silences another,” write Bowker and Star. When one point of view is silenced, it often becomes the site of contestation — a fight for visibility, voice, and political change. The boundaries of the box aren’t neutral, they’re political.

This is exemplified perfectly in the US census: In the 1990s, a group of Americans argued that “multiracial” should replace the problematic “other” category in the race and ethnicity section. This was seen as more appropriate by these advocates because, as Bowker and Star write, it would “not force individuals to choose between parts of themselves.”

But many civil rights leaders disagreed on the grounds that if everyone selected ‘multiracial’ that would mean lost information and lost resources for specific groups. Distinct categories are needed so that oppressed groups and communities receive the political and economic resources they deserve. The Clinton Administration decided that it would allow people to check more than one box but would disallow the inclusion of “multiracial.” When we check boxes in surveys, these decisions may seem inconsequential, but the boxes available to us and the ones we pick are laced with political choices beyond our reckoning.

How we fit (or don’t!) into these boxes is shaped by the technologies and their affordances. In the US Census, a paper survey forced residents to fit themselves into a binary box. In Apartheid, black South Africans were required to carry a ‘pass book’ everywhere they went, which detailed their history — work, education, marriage, other life events, etc. The passbook fastened complex histories into place. In both cases, the state apparatus did the classifying and the technologies of the day — the survey and the booklet — were used to create fixed, binary identities, torquing complex biographies into lil’ racist or simplistic boxes, and the systems could only be contested through political change.

II. You are what you click

The state hasn’t given up the power to decide what types of identification are legitimate for what purposes (e.g. passports vs. real ID etc.), but classification has become more complicated with the rise of Big Tech. Indeed, companies like Google and Facebook use algorithms to construct our respective boxes out of millions of data points (e.g. clicks and search queries), making them a lot more fluid than fixed.

In We Are Data: Algorithms and the Making of Digital Selves, John Cheney-Lippold writes,

“Who we are in this world is much more than a straight forward declaration of self-identification or intended performance. Who we are […] is also a declaration by our data as interpreted by algorithms.”

Google uses our data to classify our gender, our needs, and our values. But they aren’t actually ‘ours’ in any meaningful sense — Google owns the data and they don’t care how we self-identify. These classifications are used to computationally calculate a profile with a bunch of different categories that they sell to advertisers. As Cheney writes, “Google’s gender is not immediately about gender as a regime of power but about gender as a marketing category of commercial expedience.”

One commonality between the two classification systems mentioned so far is that they codify something in the past. Survey boxes don’t imagine how one might want to be classified, they create categories based on past and present information. Similarly, as political economist Oscar Gandy writes, “the use of predictive models based on historical data is inherently conservative. Their use tends to reproduce and reinforce assessments and decisions made in the past.”

At least with state-run systems, there’s an opportunity to question the decisions made. But we can’t easily contest our algorithmic profiles. There isn’t a public or deliberative process to determine how groups of people should be classified online. Nor is it a public official who does the classifying. Engineers, unaccountable to the public, just design algorithmic systems to maximize revenue and away we go. Moreover, a checkbox in a survey is fixed in place, affirming a boundary — whereas our algorithmic profiles are more fluid, changing a thousand times over in the course of a day.

III. You are your network

The piece I wrote about WorldCoin already gives us a little peek into how identity and classification might evolve in the context of Web3. Remember the weird orb that uses sensors to capture individual biometric data? In this case, WorldCoin and its algorithms decide what data should be used to determine the uniqueness of a person. It’s an attempt to achieve individual uniqueness but without revealing information that can then be used to sort you into groups. Put differently — it’s an attempt to break the link between identification and classification. So far WorldCoin’s path to achieving this technical milestone has involved abusing people’s privacy and collecting identifying data, which, ya know, contradicts the point.

A new concept has now emerged within Web3 identification systems: Souls (yes that’s the actual name). This uses social information — referred to as soulbound tokens (SBTs) — to achieve a similar outcome to WorldCoin. With SBTs, who I am doesn’t depend on my iris scan or my legal name; it depends on my relationships in social and professional groups, and my reputation within a network. It relies on a premise articulated by George Simmel, one of the founders of social network theory, “in which individuality emerges from the intersection of social groups, just as social groups emerge as the intersection of individuals.” In this way, those behind the idea — namely E. Glen Weyl, Puja Ohlhaver, and Vitalik Buterin — are effectively blurring the distinction between identity and classification. Your group affiliations become your identity but the group affiliations are not tied to specific identity markers.

Think of your SBTs like entries on your LinkedIn profile or Soul. You’re self-certifying that a specific credential or affiliation is legitimate — but it’s not ‘real’ until someone else can vouch for you. So SBTs are either issued or attested by other Souls. In other words, you don’t work where you work, volunteer where you volunteer, or participate in your community until someone else — an individual, a company, an organization — sends you an SBT representing that claim or validating it. The more credentials and attestations you collect, the more you can prove that you’re ‘you’ while maintaining pseudonymity.

If you’re a loyal Untangled reader, a few questions should pop immediately to mind, like:

How might this interact with existing social inequities? If someone’s identity hinges on their network, this system may not work so well for those with a limited network. Then there’s the reputation side of this: a key driver for the development of Souls is that you can identify yourself through your reputation in a network while still remaining pseudonymous. But ‘reputation’ tends to be shaped by one’s social standing. This means that Souls might inadvertently codify existing social inequities within a network.

If Souls achieve real pseudonymity, is that a good thing? Governments will still want to know who we really are, which means an SBT will unlikely substitute for a passport or other form of ID. But if I’m wrong and Souls somehow achieve real pseudonymity, that’s only a good thing if you already have power. Moreover, erasing social identity markers erases difference, which is a handy way to sidestep confronting systemic inequality. Remember how civil rights groups fought for distinct categories to ensure specific groups received the resources and representation they deserved?

How might this system contribute to unanticipated harms? The authors of this system have already discussed how bad actors or unscrupulous institutions might cheat the system and require bribes for attesting to your attendance at an event or some other action. Yeah, as someone that has researched disinformation for years, I can say with confidence: that’s definitely going to happen!

How might power show up in this system? Souls don’t remove power from the equation, they shift it from big companies or the government to your network and your community. This will be a respite for some, and a problem for others.

Still, there are some things about this idea to like: my network, the projects I contribute to, and the communities I engage with all feel like a more authentic representation of ‘who I am’ than an iris scan. More practically, it aligns with Helen Nissenbaum’s idea of privacy as ‘contextual integrity.’ Nissenbaum argues that people aren’t upset by the act of sharing information itself but the “inappropriate, improper sharing of information.” In other words, what matters is that information is shared within the appropriate context, and SBTs can be programmed differently to allow differential access, use, permissions, and profit rights to your information.

But the reason I find it most compelling is that it’s a living system that records the past yet isn’t constrained by it. As Bowker and Star write,

“We have argued that a key for the future is to produce flexible classifications whose users are aware of their political and organizational dimensions and which explicitly retain traces of their construction […] In this same optimal world, we could tune our classifications to reflect new institutional arrangements or personal trajectories — reconfigure the world on the fly. The only good classification is a living classification.”

Too often we are given prescriptive ‘solutions’ that do more to constrain our behaviors than empower us to do what we want. But Souls represent something different: a technology that actually evolves with society over time. If we do need to ascribe to some classification system, I’d rather it was one that allows me to represent myself based on my own preferences, and evolve in ways that are more directly under my control. But of course this appeals to me — I’ll be a-ok in a system that is built around one’s social position in a network and a ‘good’ reputation, and that’s not the case for the majority of people. What we need are technologies that center the perspectives of those historically at the edges of society, and that evolve as we all do, on our terms.

As always, thank you to Georgia Iacovou, my editor.